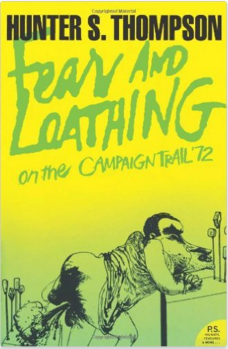

It was the most accurate and least factual account of that campaign – Frank

Mankiewicz

Well, I read the thing. Now I have to write about it.

Don’t get me wrong. It was one hell of a read. Hunter S. Thompson. The renowned (and self-proclaimed) doctor of Gonzo Journalism. Nuff said, right?

Silly me. I decided that I’d read Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail 72, and write a synopsis of it, discuss it’s merits and issues. This morning, as I sit in the one of the few dreary overcast Los Angeles days, under an unnecessary sun umbrella on the patio of a coffee shop near the 405 on the south-west side of LA, I realized the enormity of that task. [Author’s note: revisions a few days later at the same coffee shop, with sunnier skies.]

“You think you’re a good enough writer to talk about HST?” I asked myself, as the morning commuters drove by. The hum and swoosh of traffic racing by on Sepulvada Blvd bleed through the smooth jazz tweeting in my earbuds. Thompson would have his tape machine out, blaring away what we call now “Classic Rock” and not giving a damn if anyone glared at him for the noise pollution. “Pollution?” I can imagine him yelling, and hooking a thumb at the traffic in the street, and waving his hand up at “The 405” freeway traffic that is crawling by slower than the cars on the boulevard next to us. “That’s the noise pollution – this… this is artistry,” he’d cuss and crank his tape machine up to 11.

My first thought after reading Campaign Trail 72 is that I’m going to have to really dig into the history of that election. Thompson’s drug-fuelled approach to journalism – what became known as “Gonzo Journalism” and has been described many ways, but usually includes a disclaimer that although Dr. Thompson’s message on target, the gonzo approach mixes in his own retelling of stories that may be accurate only when viewed through a lens of a 60’s era heavy drug user’s imagination. What facts were real in the book? I kept asking myself.

My first thought after reading Campaign Trail 72 is that I’m going to have to really dig into the history of that election. Thompson’s drug-fuelled approach to journalism – what became known as “Gonzo Journalism” and has been described many ways, but usually includes a disclaimer that although Dr. Thompson’s message on target, the gonzo approach mixes in his own retelling of stories that may be accurate only when viewed through a lens of a 60’s era heavy drug user’s imagination. What facts were real in the book? I kept asking myself.

But then I realize: I don’t have to know the “facts” in a Sgt. Joe Friday sort of way. That wasn’t Thompson’s drive. He wanted to tell the story. The story the way he saw it. The way he experienced it in-between hits of ibogaine (and whatever other substances found their way into his bloodstream), and bursts of rage as only Dr. Thompson could perform them. Thompson’s story isn’t about facts. It’s about what happened. And only what happened as HE experienced it.

…and what got me this way was politics. Everything that is wrong-headed, cynical & vicious in me today traces straight back to that evil hour in September of ’69 when I decided to get heavily involved in the political process… (Thompson, pg. 214)

From the de-throning of “Big Ed” Muskie as the establishment front runner, to a surprise ambush on Hunter’s head by an assailant allegedly sent by Mankiewicz – these are”facts” that tell the story, that illustrates the points and themes that Thompson wants the reader to realize. This book is the political world of ’72 as Thompson saw it. Not necessarily as it really happened — but they both end up at the same place by the end of the book.

Campaign Trail ’72 isn’t really about facts, I realize. I see it as a wonderfully ironic metaphor, laced with simile, digression, characterization, and a lot of drug induced sensory details about the state of the American campaign machine in the middle of the Nixon era. He used his pieces for Rolling Stone (that were later compiled and expanded to form the book) to spread the rumors that “Big Ed” Muskie is a potential Ibogaine user, listing it’s side-effects following prolonged use as an explanation for the candidate’s erratic behavior on the campaign trail, and subsequent fall from front-runner status. “... and then the sense of depression began spreading like a piss-puddle on concrete…”

One key theme Thompson builds is that the campaign trail is nothing more than a reflection of American culture at the time. Decadence and corruption was how the establishment saw the free-love, flower power freaks of the 60s drug culture. But the reverse was also true. The freak culture saw the same characteristics in the power elites. Thompson’s own attempt at running for Sheriff in Colorado on the Freak Power ticket in 1969-70 gave him an interesting perspective on elections. He even shaved his own head bald, in order to refer to his opponents, with their militar short crew-cut hair, as his “long-haired opponents.”

Thompson’s famous quote… The Edge… there is no honest way to explain it because the only people who really know where it is are the ones who have gone over … shows how in tune he was was dallying near the edge himself. His own lifestyle, full of drug use and excessive alcohol consumption let him play near that edge, and he seemed to be telling me, in Campaign Trail ’72, that the American political system was at the edge as well. Not so much with the drug culture, but with the quest for power. In McGovern, Thompson saw the “outsider” candidate – of the kind that future Presidential campaigns tried to position themselves as. Muskie, Nixon, Humphrey, all insiders to Thompson.

I wonder what the good Gonzo Doctor would have said about the McCain vs Obama race in 2008? I admit, this is a digression similar to Dr. Thompson’s infamous “rants” that he warns readers of before spending pages off on a tangent that eventually ties into his main theme. I’ll try to keep my own digressions much shorter than Thompson’s.

Both McGovern in ’68, and McCain in ’08 were Senators, both positioned as outsiders. Thompson dives into the perception of the candidate as a theme, and how the VP selection altered the prevailing perception of McGovern’s campaign.

‘Perceive’ is the word that became in the ’72 campaign what ‘charisma’ was for the 1960, ’64 and even the ’68 campaigns. ‘Perceive’ is the new key word… The best example of how perception can drastically alter a campaign is the difference between, for instance, how McGovern was perceived by the Wallace voters in the Wisconsin primary as being almost as much of a maverick and an anti-politician as George Wallace himself… (Thompson, 1972 p. 402)

Following McGovern’s disastrous VP choice of Senator Tom Eagleton, who Thompson perceived as a concession to the insiders, and the campaign’s mishandling of dropping him off the ticket due to leaked information about Eagleton’s prior shock therapy treatments for his mental health, Thompson elaborates:

The Eagleton affair was the first serious crack in McGovern’s image as the anti-politician. … The Eagleton thing is worth looking at for a second in terms of the difference between perception and reality. McGovern was perceived as a cold-hearted, political pragmatist who dumped this poor, neurotic, good guy from Missouri because he thought people wouldn’t vote for him because they were afraid that shock treatments in [Eagleton’s undisclosed mental health] past might have some kind of lingering effect on [Eagleton’s] mind… (pg. 403)

As I read through Thompson’s account of how the McGovern campaign reacted and how those actions, Thompson believed, destroyed McGovern’s “outsider” political status, I started drawing parallels to the McCain campaign of ’08.

McCain selected Sarah Palin, then Governor of Alaska, and viewed as a fellow “maverick” [McCain’s own political title] known for bucking the establishment, for his VP running mate. As her inexperience became “perceived” as incompetence and pressure began to mount from his party’s establishment pundits began calling for her removal from the ticket. Was McCain trying to avoid a repeat of the second half of the “Eagleton affair” that Thompson talks about the perception of McGovern “as a cold-hearted, political pragmatist who dumped this poor neurotic good guy…“?

Enough digression. Back to Campaign Trail ’72 and Thompson’s story telling as just one “version” of what really happened.

One incident, on board the “Sunshine Special” – Muskie’s campaign train – involved an obnoxious drunk rube which Thompson declares he had no intention of willfully inflicting upon the candidate. The drunk, who Thompson claims to have met the night before the incident, and refers to as Chief Boohoo, boarded the train with Thompson’s own press ticket. Thompson writes of a conversation with “a New York reporter assigned to the Muskie camp” who relayed the story to him.

Abusing reporting is one thing — hell, we’re all used to that — but about halfway to Miami I saw him reach over the bar and grab a whole bottle of gin off the rack. Then he began wandering from car to car, drinking out of the battle and getting after those poor goddam girls [college aged campaign volunteers]. That’s when it got really bad. (pg. 100)

The Boohoo not only was rude and outlandish aboard the train while it was underway, but also heckled and cajoled Big Ed at a campaign stop.

It was at this point—according to press reports both published & otherwise—that my alleged friend, calling himself “Peter Sheridan,” cranked up his act to a level that caused Senator Muskie to “cut short his remarks.”

When the “Sunshine Special” pulled into the station at Miami, “Sheridan” reeled off the train and took a position on the tracks just below Muskie’s caboose platform, where he spent the next half hour causing the senator a hellish amount of grief—along with Jerry Rubin, who also showed up at the station to ask Muskie what had caused him to change his mind about supporting the War in Vietnam. (pg. 101)

Thompson weaves this scene in and out of several chapters, referencing it again and again, adding new details as he references Muskie’s decline in status. The metaphor he seems to develop about establishment politicians is summed up when he quotes H.L. Mencken: “The only way a reporter should look at a politician is down.”

Speculation abounds about the Boohoo Incident. Peter Sheridan seems to be a real person. He is detailed in Willie Nelson: An Epic Life, although “Chief Boohoo” is reported to have had ties with the Hells Angels, the group Thompson had written about earlier in his career. We’re left wondering about Thompson’s initial connection to Sheridan, and how much of the episode was engineered by him. Thompson mentions in a footnote that during the Watergate investigations, the Muskie camp tried to link Thompson and the Boohoo back to the Watergate CREEPS as a way to “humiliate Muskie in the Florida Primary.

What happened, according to Chitty, was that “the Boohoo reached up from the track and got hold of Muskie’s pants leg—waving an empty glass through the bars around the caboose platform with his other hand and screaming: ‘Get your lying ass back inside and make me another drink, you worthless old fart!’”

(pg. 102)

Would Thompson have planted Sheridan there, hoping to cause a scene? After reading Campaign Trail ’72, my intuition says possibly – better make that probably. Did Thompson miss the train on purpose? In order to claim innocence later, or did he want to be there to see the fireworks himself? Neither matters, though both are possible. Thompson, however, manages to use the scene over and over again in his (mostly) bi-weekly pieces for Rolling Stone, which later were woven together with interview transcripts and additional work to become Campaign Trail 72.

Is the Boohoo, I’ve wondered, Thompson’s metaphor for the campaign trail itself? The American public want to see something other than the safe and sanitized campaigns that the media was reporting? Is the American public wrapped up in the booze swilling, loud and boisterous heckler? Or, is this just Thompson’s own alter ego finding a way to vent by engineering an event to allow him to write about the incident?

The actual campaign of ’72 was a transition period, even without Thompson’s commentary on the times. Two sea changes had occurred in the decade prior to the campaign of 1972. First was a shift to a voter driven primary system, instead of party bosses as the primary mechanism to select each party’s candidate for President. Thompson details how this change affected the campaigns in the battle between McGovern and Humphrey, each trying to hit their magic number of delegates in order to secure the nomination.

Even with the primary mechanism, there was still room for fighting. Some states proportioned their delegates based on the popular votes for each candidate, and some were winner take all (like California). Rival factions of “delegates” from outside of the recognized winner-take-all states. Both camps needed to get their delegated “seated” as legitimate voting delegates. Thompson was able to weave this struggle between the Humphrey and McGovern camps into his narrative with a masterful narrative through McGovern’s press secretary Frank Mankiewicz. This process has become fairly sanitized in recent election cycles, but we’ve seen potential credentialing fights for the likes of Ron Paul delegates at the GOP 2008 convention.

The other sea change was how campaigns were covered by the media. Ted White’s Making of the President series of books, beginning with the 1960 campaign changed how reporters and editors viewed campaign reporting. Tim Crouse, in his Boys on the Bus book details how editors began telling their reporters to go more in depth with background stories, and look for things that will be in Ted White’s next book on the campaign trail.

This quest for insider stories, according to Crouse, was in conflict with what the campaigns wanted to get out as their message for the campaign season. White was given special access because his work was to be published AFTER the campaign, when it wouldn’t interfere with the campaign’s message during the election cycle. But, with political reporters trying to get the same access, and tell the same stories as White during that cycle, campaigns became reluctant to share as much as White was able to get from them. (Crouse, 1972 chapt 2)

This seems to me, to be where Thompson’s Gonzo style excelled. His ironic discourse, full of metaphors of the time, even with dubious veracity, become the voice trying to understand the meaning behind the messages. The metaphors of a drug and booze fueled gonzo reporter spoke to the meaning that we seek to understand – particularly of the Boohoos who run our government, control our taxes, our military, and have the potential to limit our freedoms.

The 1972 presidential campaign is beginning to feel more and more like the second day of a Hell’s Angels Labor Day picnic. (Thompson, 1973)

——-

Works Cited

Thompson, Hunter S. 1972 Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72

Crouse, Timothy 1972 The Boys on the Bus

White, Theodore, 1961The Making of the President 1960

Video: Panel discussion on the campaign of 1972 with HST, Mankiewicz, and others https://youtu.be/a203s39qPuI