Steve Schwartz has a wonderful (NSFW-Language) essay about what we know and what we don’t know. In a nutshell, there are three types of knowledge:

- Sh*t we know

- Sh*t we (know we) don’t know (SWDK)

- and Sh*t we don’t know that we don’t know (SWDKWDK)

Seems simple. We know some sh*t. We are aware there is sh*t we don’t know. But, there’s the stuff we have no fricking clue we should even be aware of (SWDKWDK). Schwartz points out in his piece that our ultimate goal isn’t to learn everything we can – that would be too monumental of a task. Instead, we need to become aware of what we don’t know we don’t know – thereby moving it out of the SWDKWDK category, and into the basic SWDK category. Once we know we don’t know that – we can decide whether we want to learn about it?

Death of the artifact: what we don’t know

Blogger and publishing futurist Craig Mod notes in his Big Do lecture that Jan 27, 2010, was the “death of the artifact.” What happened on that day? Apple released the iPad. The artifact, the printed book as a mass market entity and primary means of publishing information to fill in the SWDK gaps, moved onto the road to obsolescence.

The iPad and the age of tablet information dissemination it unleashed weren’t the death of the newspaper, journalism or the book. BUT, it was the beginning of a vast sea change in how those artifacts and professions were going to be consumed. The change didn’t begin with the iPad. It has been coming for quite some time. The internet has provided the largest shake-up in the delivery of SWDK to the masses. With each new addition to the technology, we begin a new cycle of not knowing what we don’t know yet. Not only can we not see immediately how the new tech will change the various parts of the publishing world, we don’t know what tech is around the corner, and how that will affect what we just realized we don’t know yet. More Sh*t we don’t know that we don’t know.

The internet provided one key ingredient to the publishing world, whether we’re talking about journalism, music, fiction, narrative non-fiction, or just about any other field of SWDK: independence from the corporate control avenues of what get’s published. Jessica Bell has an interesting viewpoint in a column on indie publishing.

The industry has changed, forced into embracing the digital revolution, just like the music industry. Independent artists are everywhere now. Authors don’t self-publish because they’re too lazy to go through the slog of submitting queries to agents, or editing their manuscripts properly, or simply out of impatience to see their work in print, just like independent musicians aren’t too lazy to find a record deal. They simply have a different sound. Or they don’t want to be told by the record label what they should and shouldn’t record. In a saturated market, where publishers/music producers have millions and millions of queries and proposals, independent artists are driven by self-belief and a passion that their work deserves a place.

Let that sink in for a moment. “in a saturated market…” the internet opened up the markets. We went from four main television news networks pre-cable TV era to many CNN, MSNBC, FoxNews et al. Add in the impact of the digital age and the interwebz, and every market everywhere is suddenly open to over-saturation if one looks only at the old business models. I saw this first-hand in the wedding and portrait photography industry. Once digital cameras, computers, and easy dissemination of images through digital means came about, the old film-based learning curve for photography went out the window. No longer did photographers have to have SWK knowledge. They didn’t have to wait a week to get their film back to make sure they didn’t screw up. Digital cameras gave instant feedback, and moved information in the wanna-be photographer’s circle from SWDKWDK about how to set the camera into SWDK but can learn circle. Fake it til you make it became the buzzword. Everyone became a “professional photographer” as soon as they got a digital camera and saw, and learned from, their photographic mistakes in real time.

That looks like crap, what happens if I change this setting? much better! I’ll figure out why later.

Publishing – whatever field – is in the same boat. The indy artist, writer, photographer, etc is free to publish outside of the corporate world.

Craig Mod, in his Big Do lecture, talks about his 2nd go at publishing his Art Space Tokyo book. He’s also got a blog post dissection of how he funded an independent publishing attempt AFTER he had a short run professional publication of the same book. His secret? Use the Internet to generate interest, fund, and market the “artifact” publication. He used Kickstarter, after some intensive research on how to succeed with it, to fund his purchase of the publishing rights, and the initial run of publication of the work.

What is interesting is that the “artifact” of a printed book, which he declared dead earlier in his lecture, became the artifact he successfully sold using the tech of the internet and digital revolution in printing. His artifact wasn’t just a printed book – but a specialty niche publication, with specialty (silk screening) publication technology. More SWDKWDK developed, almost in reverse – how to successfully fund the printing of, and sell an almost extinct artifact in the independent publishing world. Application of expanding tech to create online, independent financing was SWDKWDK a few years before. Applying it in creative ways moved it mostly into the SWDK area, but will the next innovation have the potential to give even more undiscovered opportunities. If we’ve learned anything from the digital revolution, we can safely say: probably.

Niche publication

As I indicated above, we’re seeing over-saturation in many traditional markets and professions. Whether we’re looking at indie book publishing, the plethora of news outlets, blogs, wedding photography, music, et al, they all are devolving in some ways – and heading back away from “mass” and into niche works.

Case Study: Mantic Games

When we’re talking about gaming, as in the table-top variety, not the gambling variety, nor the computer/online/e-box versions – the industry has been niche oriented for a long time.

In my personal world, I’ve experienced long-term association as player and organizer of events in both the role-play (e.g. Dungeons and Dragons) and the miniature wargaming niches. My current involvement is in the miniature wargaming field, with hours spent painting little “toy soldiers” and their various bits of equipment. These miniature table-top battles are usually in one of two broad categories: Historical or Fantasy.

The historical miniatures take a set historical period and create a set of rules to approximate the battlefield conditions and tactics of that period. I’m currently playing a WWII based game, but other periods, such as the US Civil War, Napoleon’s battles, The Great War (WWI) or even many of the ancient periods are all popular in this sect, making a wide variety of niches.

In the fantasy world, one can find futuristic, or more ancient-fantasy, a la Lord of the Rings style with orcs and dwarves and elves. Steampunk, a combination of Gothic Sherlock Holmes time period meets steam powered futuristic tech, is also popular.

How does the web and it’s methods of reaching consumers directly help or hinder the numerous small gaming manufacturers and publications? A small case study can show how one game company is utilizing the web to help their business model.

This company exists in the fantasy table-top wargaming niche. It was founded to produce the artifacts (the actual models or “miniatures”) for a profit. Knowing that they were competing in a saturated market, already dominated by a few major players like Games Workshop, providers of the Books and Miniatures for their line of games, Warhammer Fantasy Battles, and Warhammer 40K (Fantasy Space battles).

The owner of Mantic worked with freelance modelers and sculptors to create his lineup of models. Rather than offer them solely to be used in other game systems, Ronnie Renton, the owner, teamed up with a former Warhammer game designer, Alessio Cavatore, and created the Kings of War fantasy rule set.

Kings of War broke the model of artifact game publishing in several ways. First, Renton and the game rules designer Cavatore reversed the trend set by Games Workshop of a lengthy, involved rules set. Instead of producing a weighty tome of several hundred pages (about 100 of which were actual rules for the game), the Mantic rules were a mere 16 pages long.

Mantic also changed the mold in what they tried to sell to gamers. Big producers in the field produced rule books, accompanied by companion “army books” as well as lines of miniatures to use in the game. Renton, at Mantic, gave his rule away for free to stimulate the gamer’s ability and desire to purchase his artifacts – the actual miniatures for the game table.

After getting started, Mantic then went a step further and used the Craig Mod idea. New lines of miniatures that they wanted to produce, or entirely new game sets, and even a hardcover full sized artifact rule book for Kings of War, were announced and funded by way of Kickstarter.

Renton made his first officering via Kickstarter by announcing his Kings of War boxed set of the hardcover rulebook and two armies of miniatures in the box. Despite having a rule book in the set, he kept the Kings of War basic rules on-line, offered for free. Players didn’t have to purchase the rule books, or accompanying army specific rulebooks to play the game. In the Kickstarter promotional video, Renton states that he’s seeking funding through Kickstarter to speed up his production timetable, and grow the offerings (add new army variants) to the game system.

The way Kickstarter works is that a goal is set for the project. Consumers interested in the project pledge monetary support, in effect pre-purchasing the product at one of several pledge levels. The base amount is for the base product. Higher pledge amounts give the consumer more goodies from the company for their increased level of support. The goal is to at least fund the project at 100% to initiate the payment of the pledges to the company. Once that goal is reached, the company can offer added incentives to increase exponentially their funding. This uses a crowdfunding model where sharing the information about the project can add more product to existing pledges, as well as increase the various pledge levels.

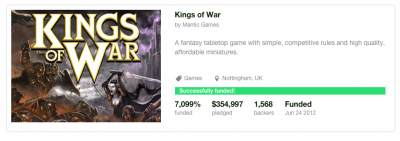

Renton and his Kings of WarKickstarterr took advantage of the changing model of how independent publishers were funding their project start-ups. His Kickstarter for this project reached a 7,000+ % funding goal, with 1,5000+ supporters, and over $350,000 raised for his project. Eight more successful KickStarter projects followed, including a 2nd edition of the original Kings of War boxed set.

In a market where the large game companies were raising prices on both mandatory books, and the miniatures to play the games, following a model of planned obsolescence for their various miniatures to get players to purchase newer ones, Renton and his company changed the model by publishing their rule set free, and going directly to their consumers to fund their growth.

Renton embraces the SWDKWDK business model, breaking past established models, and crossing barriers in funding and distribution that the web had recently enabled. By taking his company outside of the traditional business model everyone knew, and looking for ways to move his product and grow his consumer base, he succeeded in a small niche market against larger companies with established consumer bases.

What’s next for indy-publishing, whether it’s a digital product, or an artifact like an art-book or a new game? That’s SWDKWDK… yet.

[…] same product can lead to different routes for and effects of the same underlying media product. In my previous essay, on Sh*t We Don’t Know We Don’t Know, I discussed how Mod crowd-funded the publication of the […]